Share This article

Physics is unique in the scientific world, in that its reliance on math means it can come to a broad consensus on matters with very little evidence available. In Earth science, a veritable mountain of evidence can’t fully bury the issue of global warming, and even with the vast majority of scientists now convinced, a vocal minority still dissent. Yet in the case of physics and dark matter, a substance defined as being virtually immune to observation, there are no meaningful dark matter deniers left standing. So what is dark matter, and how has physics come to such a powerful agreement on the idea that it makes up the vast majority of matter in the universe?

Matter, the regular kind that makes up the atmosphere, the Sun, Pluto, and Donald Trump, interacts with the universe in a number of ways. It absorbs, and in many cases emits, electromagnetic radiation in the form of gamma rays, visible light, infra-red, and more. It can generate magnetic fields of various sorts and strengths. And matter has mass, creating the force of gravity, the effects of which can be readily observed. All these things make matter convenient to study, in particular its interactions with light. Even a black hole, which emits no light, blocks light by sucking it in — but what if the light coming from behind a black hole simply passed right through, and on into our telescope lenses? How would we ever have proven the existence of a black hole, in that case?

All these things make matter convenient to study, in particular its interactions with light. Even a black hole, which emits no light, blocks light by sucking it in — but what if the light coming from behind a black hole simply passed right through, and on into our telescope lenses? How would we ever have proven the existence of a black hole, in that case?

That’s the situation physicists face with dark matter. Dark matter does not seem to interact with the universal electromagnetic field in the slightest — that is, it does not absorb or emit light of any kind. In fact, dark matter seems only to interact with the universe as we can observe it through a single physical force: gravity. So, in the case of our invisible black hole, we might have been able to notice it by seeing how light coming to us from a certain section of sky was bent relative to our expectations, knocked slightly off course by passing close to an object bending the surface of the spacetime it’s traversing. Adding up enough light-bending observations, scientists could probably figure out the position and even mass of the invisible singularity.

So, in the case of our invisible black hole, we might have been able to notice it by seeing how light coming to us from a certain section of sky was bent relative to our expectations, knocked slightly off course by passing close to an object bending the surface of the spacetime it’s traversing. Adding up enough light-bending observations, scientists could probably figure out the position and even mass of the invisible singularity.

However, dark matter is harder to study than even that, because it does not come conveniently clumped into super-dense balls like stars and black holes — that would be far too easy. Instead, the primary theory of dark matter says that it is made of hypothetical particles called Weakly Interacting Massive Particles (WIMPs), which are about as well understood as their catch-all name implies. WIMPs don’t even seem to interact with each other through anything more than gravity, meaning dark matter does not fuse to form larger or more complex molecules, and remains in a simple and highly diffuse gas-like state.

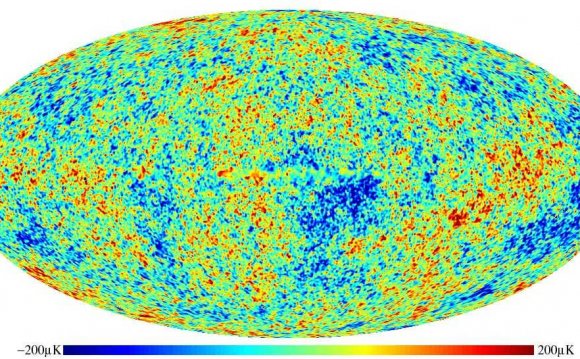

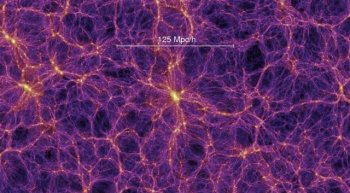

Thus, dark matter’s gravitational impact is extremely spread out and, it turns out, can only be observed when we look at the large-scale distribution of visible matter in the universe — things like galactic super-clusters, and the corresponding super-voids. It’s theorized that after the Bing Bang, the properties of dark matter would have led it to settle down far more quickly than regular matter, going from a totally uniform gas-cloud to a somewhat clumped network of smaller clouds and connecting tendrils. These tendrils can stretch across the universe; the distribution of dark matter soon after the Big Bang is thought to have directed where regular matter eventually collected, and thus where and how galaxies formed.

INTERESTING VIDEO